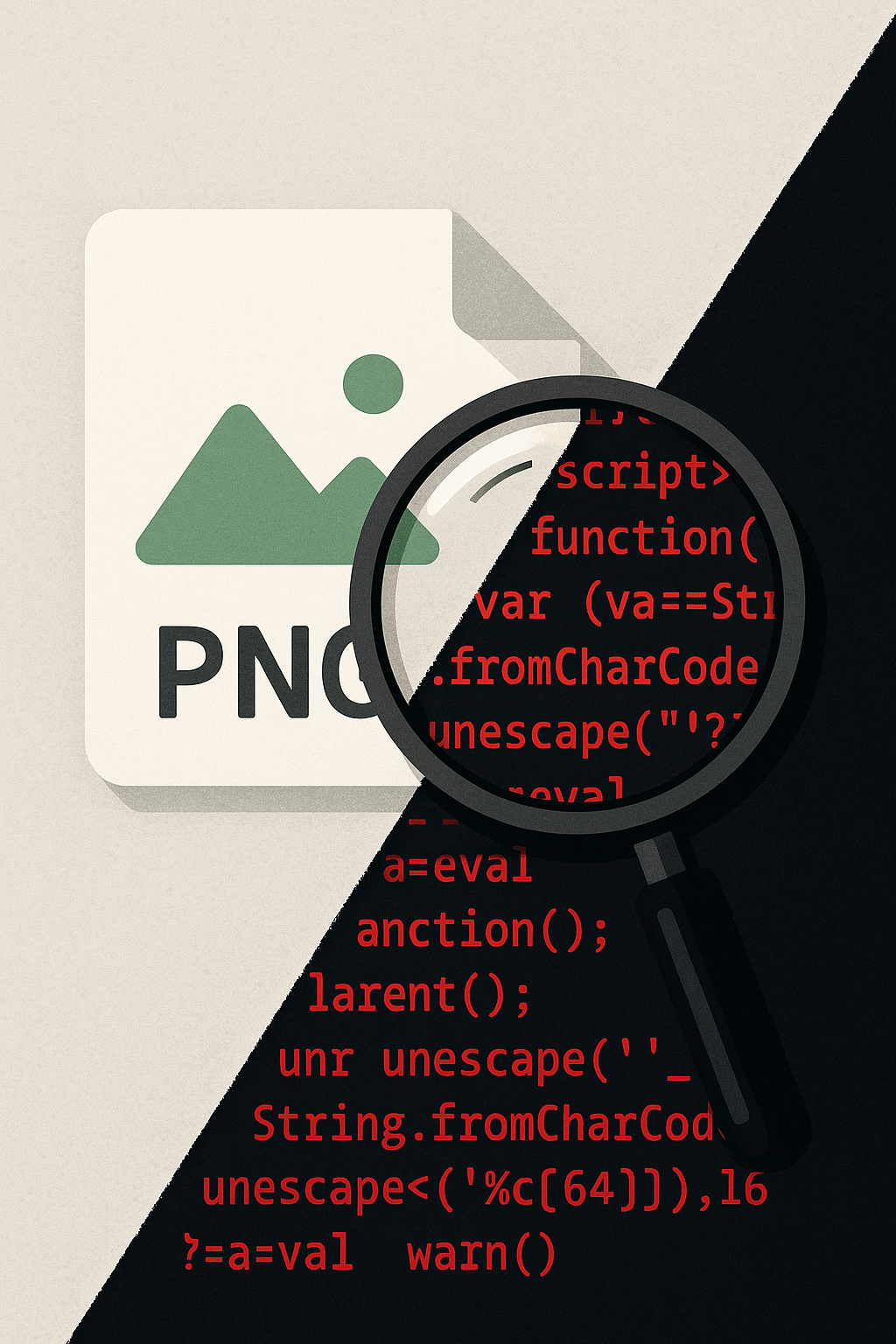

By: Karrie WestmorelandThat PNG attachment in your inbox might be more than just pixels.

There is a new breed of file-based threats. One showed malware hidden inside PNG images, appended after the end-of-image marker. Another demonstrated alternate data streams in Windows, which can smuggle scripts alongside innocent files. Both share one goal: hide payloads where defenders are not looking.

Steganography is as old as espionage itself; once done with invisible ink, now done with pixels. In cybersecurity, it means hiding malicious content inside image files without breaking how the image looks. To the user, the cat meme is just a cat meme. To the computer, it may carry a command-and-control beacon or a downloader.

Modern malware developers love steganography because:

- Image files are trusted and everywhere in business workflows.

- Firewalls and email filters rarely flag a PNG or JPEG.

- The hidden payload is often encrypted or compressed, making detection even harder.

One campaign demonstrated this perfectly: a PNG carried an appended script after its “end of image” marker. To humans, the picture opened fine. To the loader, those extra bytes meant executable code waiting to run. Families like Zeus, Ursnif, and Trickbot have all dabbled with steganographic loaders to sneak past security tools.

Alternate Data Streams (ADS) exploit a feature of NTFS that most users, and many defenders, don’t know exists. ADS lets a single file carry multiple data streams, with the hidden streams invisible to normal directory listings or file properties. Think of it like a secret notebook taped to the back of a book.

Threat actors use ADS to:

- Hide PowerShell scripts inside everyday Word documents.

- Store persistence mechanisms in system files like desktop.ini.

- Smuggle secondary executables alongside legitimate installers.

One real-world example: a benign-looking text file with an ADS stream that contained a full-fledged backdoor. Casual inspection showed nothing unusual. Only by listing streams with specialized tools could defenders uncover the payload.

Different tricks, same strategy: disguise the danger inside the ordinary, knowing most defenders won’t peel back the layers.

Old advice such as “do not open suspicious attachments” fails here. These files do not look suspicious. They pass casual inspection, display properly, and often evade antivirus scans because nothing appears overtly wrong.

For example:

- An image of a corporate logo can also carry a remote access Trojan hidden in its padding

- A Word document passed between colleagues can quietly include an ADS storing a malicious script

- Even downloaded installers can carry secondary streams invisible to most endpoint users

This means defenders cannot rely on visual inspection or standard signatures. The threats live in the blind spots.

You cannot fight what you cannot see. Defending against these techniques means digging deeper than the surface:

- File inspection: Yara rules can be crafted to flag unusual markers, trailing code, or patterns consistent with steganography.

- Stream analysis: Tools such as streams.exe or cut-bytes.py can list and extract hidden alternate data streams.

- Sandbox detonation: Executing files in a safe, controlled environment lets defenders see behaviors that static inspection misses. If a PNG suddenly spawns a PowerShell process, you have your answer.

- Training analysts: Analysts need to learn how to spot anomalies in file headers, metadata, and structure. Malware families like Zeus, Ursnif, and Trickbot have all dabbled with steganographic techniques. Knowing their tricks makes detection easier.

These attacks blur the line between everyday detection and digital forensics. Instead of just asking “is this file clean,” analysts must ask “what else could this file contain.”

Some practical examples from the field:

- A PNG embedded in a phishing email carried a base64 encoded PowerShell payload at the end of the image. Opening the picture was safe, but a script parsed the hidden code into an active downloader.

- A Word document marked with a “safe” icon carried malicious JavaScript in an alternate data stream. The stream executed only when the file was processed in a certain way.

- Adversaries have used ADS to smuggle persistence mechanisms, hiding scripts under desktop.ini files where few defenders think to look.

This is why defenders need tools, skills, and a mindset shift. File analysis is not just for malware researchers anymore. It is frontline defense.

For leadership, the takeaway is straightforward. File-based threats are not just a technical problem. They are a business risk hiding inside the documents, images, and workflows your organization depends on daily.

Investing in deeper detection capabilities may sound like an IT cost, but it is really a business continuity safeguard. A malicious script hiding in a contract, invoice, or design file can lead to the same outcomes as a ransomware outbreak: downtime, lost trust, and damaged reputation. The cost of prevention is measured in tools and training. The cost of failure is measured in millions.

If you only look at the surface of a file, you will miss the real story. Malware thrives in hidden corners: image padding, metadata, and alternate data streams. Treating files at face value is no longer enough. This is not paranoia. It is 2025 reality.

How confident are you that your tools, and your people, can spot malware hiding in plain sight?

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Get updates and learn from the best

More To Explore